Ideologically Out of Line and Insufficiently Diverse

On identitarian social justice ideology, independent film nonprofits, and a scandalous documentary film stuck in distribution limbo

“Tell people that they are inferior, they are unlikely to be pleased, but this surprisingly rarely leads to armed revolt. Tell people that they are potential equals who have failed and that therefore, even what they do have they do not deserve, that it isn’t rightly theirs, and you are much more likely to inspire rage.”

David Graeber, Debt

We must not seek to use our emerging freedom and our growing power to do the same thing to the white minority that has been done to us for so many centuries. Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man. We must not become victimized with a philosophy of black supremacy. God is not interested merely in freeing black men and brown men and yellow men, but God is interested in freeing the whole human race. We must work with determination to create a society, not where black men are superior and other men are inferior and vice versa, but a society in which all men will live together as brothers and respect the dignity and worth of human personality.

-Martin Luther King Jr., Give Us the Ballot (1957)

Martin Scorsese, Clint Eastwood, Christopher Nolan, David Fincher, Steven Spielberg, Wes Anderson, Ridley Scott, Danny Boyle, The Coen Brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson, Edgar Wright, Guy Ritchie, Richard Linklater, David Lynch, and, sure - why the hell not? - Roman Polanski.

It seems like you can’t shake a stick in Hollywood (or even on the international scene) these days without coming across an old white guy director. These guys are all over the place, in theaters and on Netflix and HBO, swarming like flies in the faces of those who would deign to demand a little diversity in the film business.

So, how could the straight, white man writing this essay possibly think that white men, of all people, are now dealing with systemic discrimination in the context of filmmaking?

Certainly this author is mad, or some sort of secret Nazi, hell bent on holding women and people of color back from what’s rightly theirs so that he can establish a new Fourth Reich. After all, what sort of lunatic would assert that white male film directors might not be getting a fair shake, given the way our culture celebrates the old, white men listed above?

Well, I don’t think the average film viewer is particularly well acquainted with the various processes by which directors weave their ways into these celebrated positions in the first place. Everybody has to start somewhere, and the starting line for film directors has changed drastically in recent times.

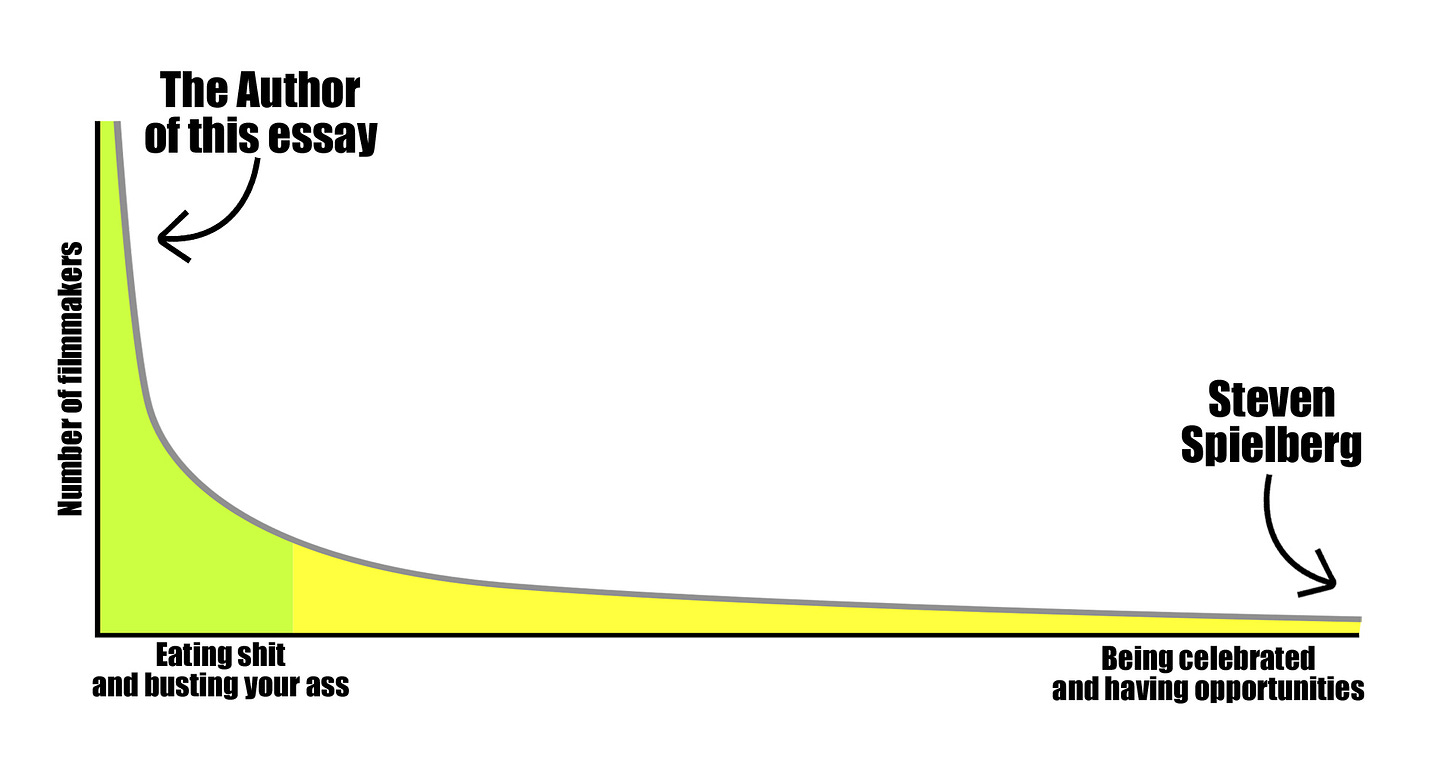

This is an essay about the extremely long tail of the independent film business. For every Scorsese, there are thousands of filmmakers who’d be all too happy to take his place - some talented and others not - and for those who hope to even begin to establish themselves, the game has changed completely.

So what’s been going on with the left half of this chart in recent times? How does all of this relate to race and gender? Well, you may find yourself surprised that white men are now, in many regards, at a stark disadvantage over there. People have been understandably upset with the conspicuous lack of diversity among Spielberg and his ilk, but institutions are now going about trying to correct that by loading the dice along identitarian lines among filmmakers who are struggling to get anything off the ground.

We’ve all heard a great deal about DEI. Either it’s going to save this country from its racist, sexist history once and for all, or it’s going to lead to the downfall of the west, ushering in a new dark age that we won’t recover from for centuries, depending on who you ask.

I’m not going to try to tackle that issue in its entirety here, but let’s have a look at what’s been happening in the world of independent film in recent times, and specifically at the various nonprofits and foundations that make it their mission to nourish and cultivate young talent.

Not all of this is a simple matter of race and gender checkboxes. So far as I can tell, a significant aspect of what’s going on here has to do with favored and disfavored narratives in the context of an ideology that’s begun to function as a new civil religion.

So if you’re intrigued and you’ve got the time to read this 10,000+ word piece, bear with me. I promise I’m not a Nazi.

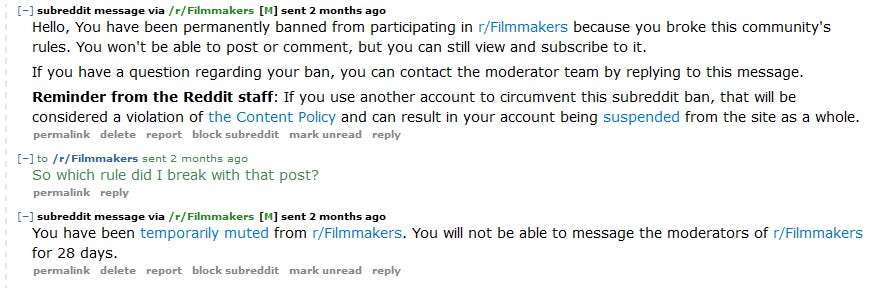

A few weeks back, after a couple of drinks on a Friday night, I shared this Film Industry Watch article about gender politics in the film industry on the filmmakers subreddit. My approach to titling the post was admittedly provocative: “So, how are we feeling about the way that so many grants, fellowships, labs, and festivals are clearly rigged against white guy now?” I asked.

I expected flak. I expected pushback. I expected to be sneered at a bit. I expected some people to assume that I was a talentless hack blaming women and people of color for my own shortcomings as a filmmaker. I expected shaming tactics and I expected to have my character maligned. It was an experiment in bluntly calling it like I see it.

I also naively hoped for a small opportunity to discuss what I’ve been seeing now for years: a paradigm in which so many institutions that support and screen independent film appear to regularly favor anyone who’s not a straight, white, man when it comes to the dispensation of funding, mentorship, and exhibition opportunities.

As anticipated, the flak and assumptions that I was a talentless hack arrived very quickly. When I went to hit the “save” button on what I thought was a reasoned response to one of the less hostile comments, I was informed that my reply couldn’t be posted. I checked my inbox, and noted that I had been permanently banned from the subreddit. All of this had played out in less than thirty minutes.

It seems obvious at this point that there are some important questions about the cultural politics of institutions that support independent film that are effectively impossible to ask in a great many contexts; in fact it seems that these questions are more or less impossible to ask in basically all of the contexts that matter.

My suspicion is that some people who haven’t been engaged with film festivals and the various organizations that hand out funding for the arts won’t really know what I’m talking about here. If you’re not in the habit of regularly paying attention to who’s being selected for these opportunities and who’s being passed over, then I don’t blame you for being skeptical about my claims.

Sure, most people can relate to having experienced some sort of annoying diversity training at work, but at the end of the day the social justice movement is just trying to establish equal opportunity for everyone, right? Maybe some of the people involved are fumbling their way through what they’re doing, but no doubt they just want everybody to have a fair shot, don’t they? People who were once left out of various opportunities are finally getting their chance to shine. Surely, there’s nothing more to see here…

On the flipside, those who are already sufficiently established in the film industry - those who are breathing “the rarified air” at the top - generally don’t have to worry about these issues, and may not even notice them. If you’re already sitting pretty with a coterie of supporters, various influential connections, and investors who want to fund your projects, then you don’t really need to notice that new forms of favoritism, justified by social justice ideology, have arisen. Maybe your work has a proven track record of economic viability and you have a distributor that you’re used to regularly working with.

It’s possible that you might be someone on the inside who’s been noticing that things seem amiss lately. Maybe the pendulum seems to have swung too far. But in that case, you’re in something of a bind. Is it worthwhile or sensible to bring up this sort of taboo subject when your ability to create the art that sustains you, financially and maybe even emotionally, is potentially on the line? It might be better to keep your head down and just let things blow over. No need to make a hubbub or end up on the wrong end of a pile-on by acknowledging that anything might be wrong here.

It also might even be possible that you’re Richard Dreyfuss, aging and a bit rambly, possibly not even always altogether coherent, but still largely correct about the way that concerns about identity and representation have been affecting the film business and the art of cinema in recent years.

I’m not sure if I should try to cast Richard Dreyfuss in a film as a black man, but the simple truth of my predicament is that I have next to no institutional connections, and, as of late, I haven’t been able to get my work played at respected film festivals at all. I’ve been rejected by every grant, fellowship, and lab I’ve applied to over the past decade.

I guess I’m a man with nothing to lose.

While fans of Star Wars and Marvel have been complaining about wokeness infecting their favorite IPs for years, public discussions about how DEI initiatives have been playing out among the people actually working in the industry have thus far been very marginal.

As a sort of industry outsider who’s been scraping by while fruitlessly attempting to engage with nonprofit arts foundations and the like for years, I’m not particularly familiar with the ins and outs of contemporary Hollywood, but it’s clear that these issues are playing a significant role there as well. If you don’t think Disney is committed to the social justice ethos, for instance, consider what Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, slated to direct Star Wars: New Jedi Order, was up to just four years ago.

So far as I know, the way all of this has been playing out for people working in Hollywood has been confronted almost exclusively by anonymous whistleblowers.

Let’s get back to the independent scene, though.

Anybody who pays sufficient attention to the various grids of faces showing off who’s been selected for various opportunities that have been released by arts organizations in recent years, or to the statistics that film festivals release in their own promotional materials, or even simply to the culture that dominates these milieus, knows that decisions are now often being made not based on artistic excellence and merit, but on the identity checkboxes of those who are making the submissions (and, for that matter, on whether or not those making the submissions properly maintain ideological allegiance to the preferred narratives of social justice culture both in the work itself and in how they explain it). Apparently it’s not enough for there to be scads of organizations designed specifically for women and people of color; the organizations that are intended simply to support the art of cinema in general have to cater to identitarian social justice ideology as well.

It’s just that nobody’s allowed to verbalize any of this without serious risk of becoming a pariah.

From a certain point of view, it’s a tendency that comes from a good place. People want to support the underdog. They don’t want a society that’s racist or sexist. They don’t want white men to be unfairly given the upper hand, as they all too often were in the past. But how has all of this actually been playing out in contemporary practice?

While I’ve no doubt that many of the people who’ve established this new paradigm genuinely believe they’re fighting the good fight, that they’re heroically correcting a past that all too often gave short shrift to women, to filmmakers of color, and to gay and trans filmmakers, they’re nonetheless creating a set of de facto quotas that constitute a new (and all too often remarkably artistically bereft) system of racial and sexual discrimination, and they’ve arranged some very dysfunctional, even absurd incentives in the process.

Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater: demographic identity categories can be very useful. From a sociological standpoint, they can and have helped us establish simplified understandings of general trends related to various groups that have been, on the aggregate, advantaged and disadvantaged by cultural and political structures and histories. Dialogue about race and gender can be important and socially beneficial, but we also shouldn’t forget that categories are ultimately “compromises with chaos.” When systemic policy is ham-fistedly built based on these categories, it’s remarkably easy for them to result in new systems of unjust discrimination. When you eschew the complexities of the world, failing to acknowledge the experiences of individuals and flattening perceptions of reality by conceiving of human beings primarily as members of identity categories, it’s all too easy to become a new iteration of precisely what you purport to be righteously toppling.

What’s more, any analysis of class structure is almost always conspicuously absent from discussions about policies designed to assist the marginalized and disadvantaged. In this piece, we’re talking about nonprofit corporations that handle billions of dollars, so it’s easy to understand why questions of class structure, for the most part, simply haven’t been factored into the policy calculations.

At a time when the film industry is already contracting, when a new generation is less interested in movies and more interested in short-form online entertainment, when it’s difficult to get somebody to watch a movie even when you’re giving it to them for free because so many people are distracted by social media and busy with their everyday lives, and when streaming services, founded on blitzscaling models facilitated by venture capital injections, have upended the business of independent filmmaking altogether, devaluing movies and leaving most independent filmmakers staring down the barrel of receiving a few cents per view on ad supported streaming services and completely at a loss for how to find a way to continue working in an economically sustainable manner, the addition of a cult-like adherence to an ostensibly progressive ideology that constricts the horizons of artistic expression and viewpoint diversity while arbitrarily favoring some applicants over others along identitarian lines has the potential to bring down the artform as we know it.

More on that later, though. Let’s consider the specific case of an independent documentary film I’ve made.

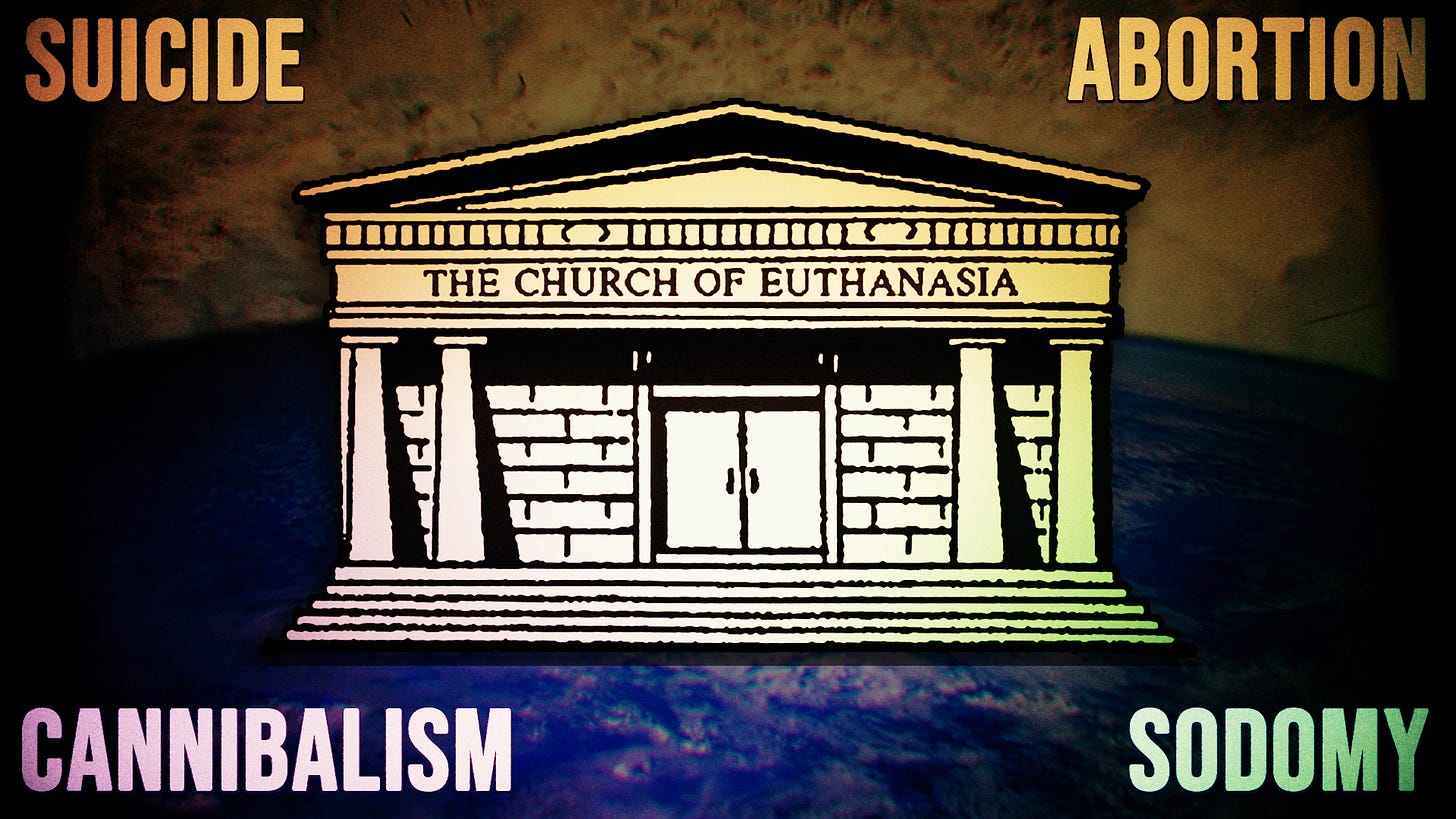

No One Left to Offend: The Rise and Fall of the Church of Euthanasia

Throughout the 1990s, a group of MIT engineers and artists lead by cross-dressing musician and programmer Chris Korda form a faux suicide cult that uses a unique blend of Neo-Dadaism, culture jamming, and media-hijacking pranksterism to provoke cognitive dissonance, challenge anti-abortion domestic terrorists, and attempt to save the planet from imminent environmental catastrophe; a meditation on outrage culture, the end of artistic transgression, and the power of controversy in a burgeoning attention economy.

No One Left to Offend: The Rise and Fall of the Church of Euthanasia is a complicated, scandalous documentary film. I don’t blame you if you can’t make heads or tails of the brief synopsis above. It’s a remarkably difficult film to describe efficiently in a paragraph or two, because it covers the activities of a very peculiar group of people. This five minute trailer might give you a better idea about what the movie is.

The film was made for less than $40,000, almost exclusively by volunteers. Like I said above, I have next to no institutional connections in the movie business. Some of the gear we used to get it made was less than ideal, and finishing it was a process that took several years. It was a beast of an edit and by the time the cut was basically finished, the laptop that I did most of the work on needed to be replaced. Still, with some clever techniques, some affordable vintage lenses, and a scrappy attitude, we were able to achieve general production qualities that rival much more expensive projects.

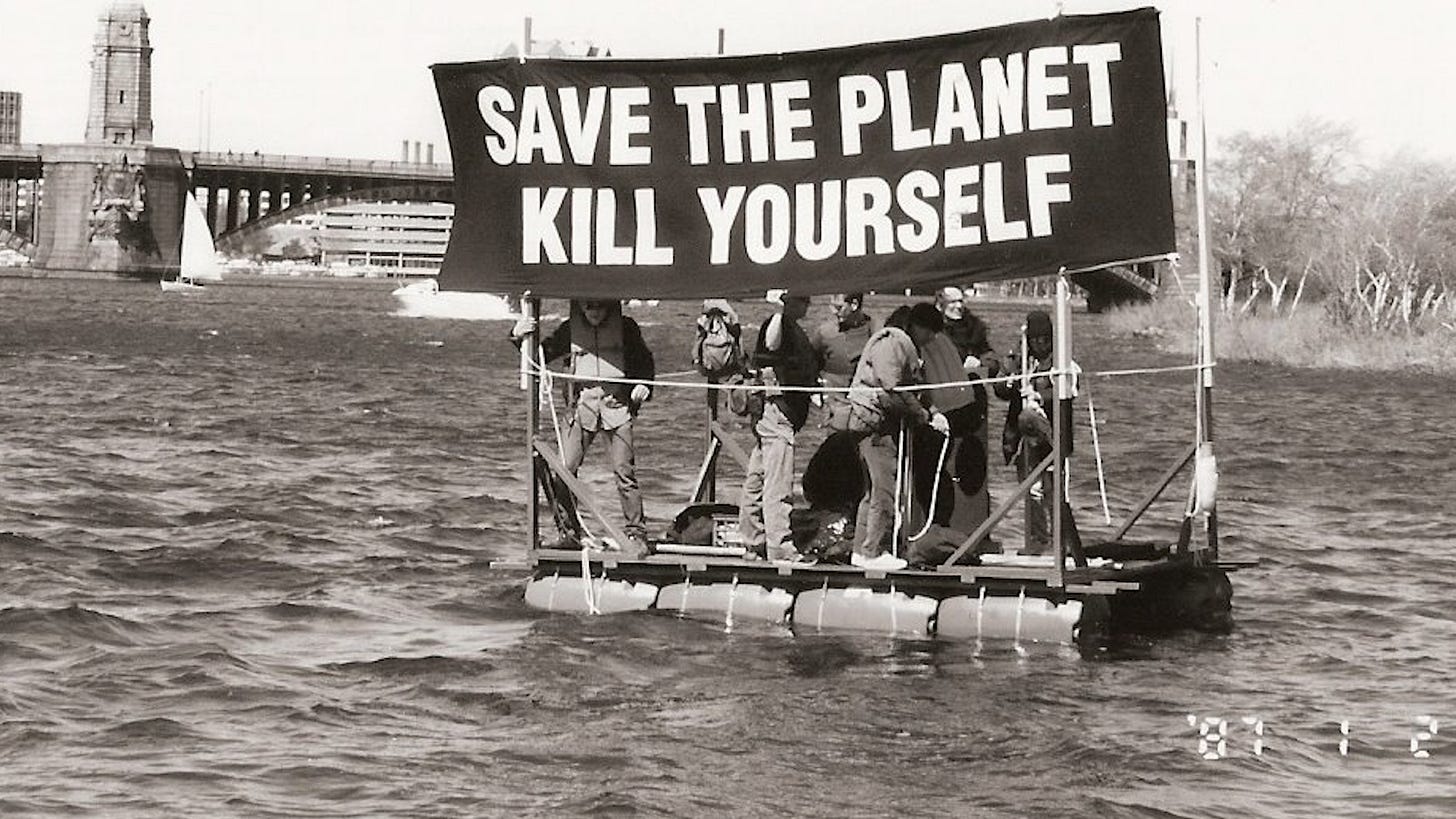

It covers a group of eccentric performance artists and MIT engineers that embarked on a very strange path: they formed a faux suicide cult back in the 90s and engaged in a variety of provocative schemes and street theater antics in order to deliberately provoke cognitive dissonance in passersby and thereby call attention to environmental issues and abortion rights. Ostensibly based on a commitment to the methods of the early 20th century Dada movement and Situationist art, the group pushed the limits of free speech, challenged the hegemony of the Catholic Church, caused a great deal of chaos and confusion, and garnered international attention by purposely stirring up outrage and controversy.

In short: they were trolling in public for a cause. But were their motivations really that simple? Human motivations are rarely clean cut.

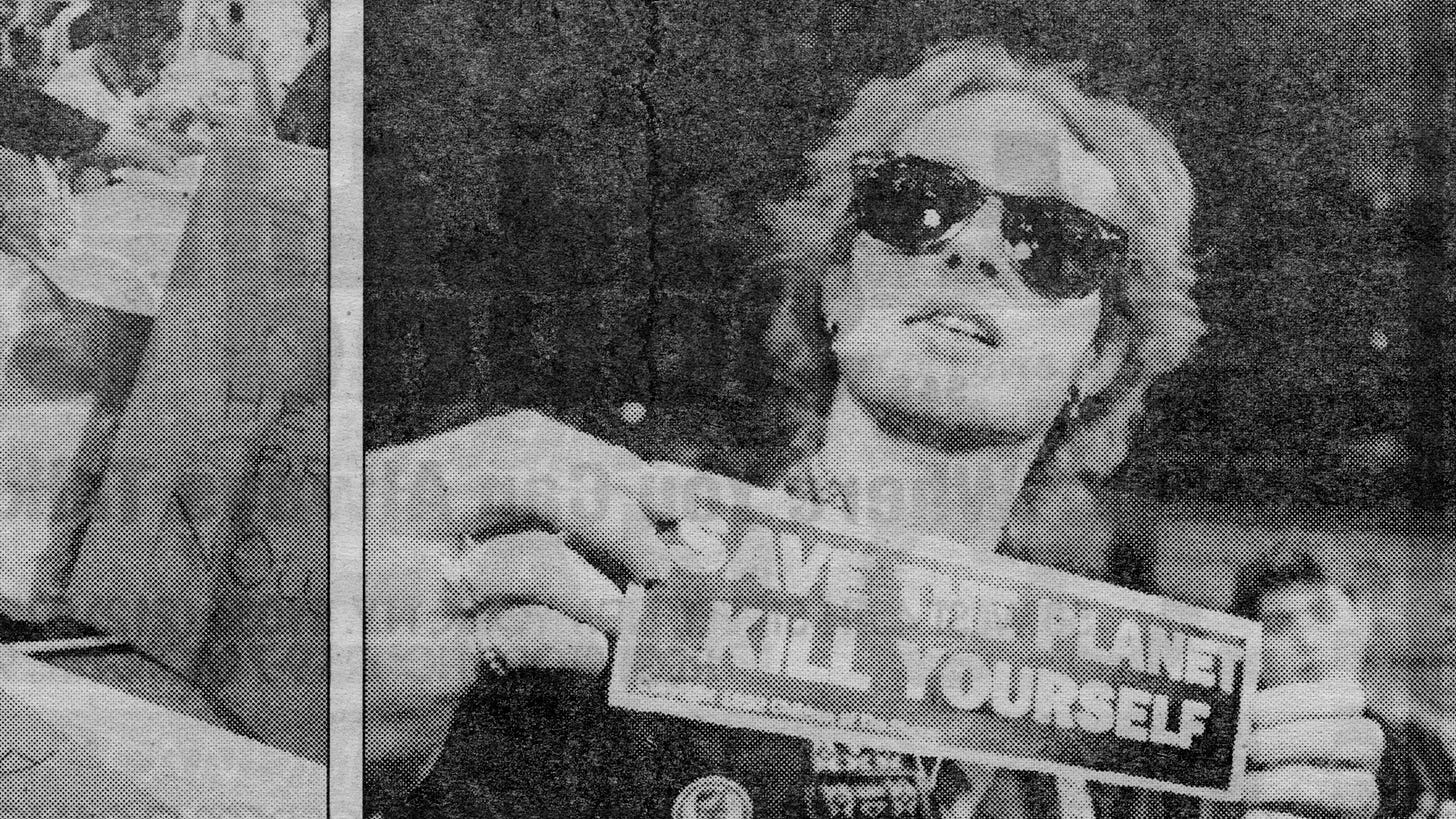

Their motto was, “Save the Planet, Kill Yourself,” which was the initial title of the film, before I thought better of it. They sold a lot of bumper stickers that said that. The four pillars of the church were “Suicide, Abortion, Cannibalism, and Sodomy.”

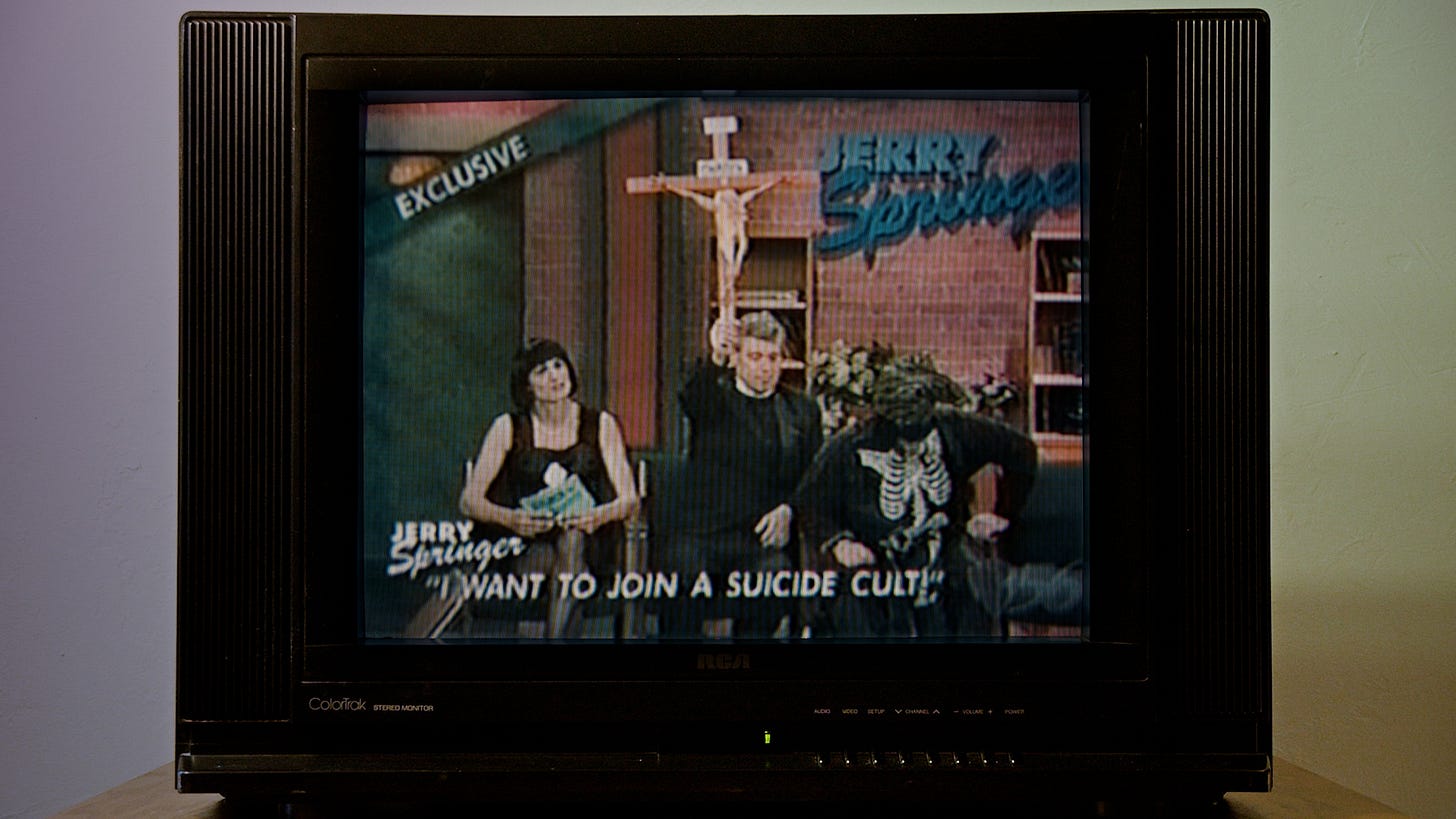

They brought baffling signs to anti-abortion protests to undermine Christian conservatives. One of them read, “Eat a Queer Fetus for Jesus.” They hosted a “fetus barbecue” on The Boston Common and publicly grilled “fetuses” made of pectin. They unveiled a giant penis puppet, complete with an internal ejaculation mechanism, outside of a sperm bank after enticing a group of nuns to join a fake protest there under fabricated pretenses. Criticizing greenwashing long before it was en vogue, they made a habit of cleverly undermining a corporate sponsored earth day festival that they decided was “littering a park for the earth.” They eventually found themselves on The Jerry Springer Show, opposite right-wing anti-abortion extremist Neal Horsley. Michael Bray, who had been to prison because of his connections to a series of abortion clinic bombings, was initially scheduled to appear on the show as well. He was moved into the audience at the last minute before shooting commenced.

There’s a great deal of over-the-top, incendiary content in the film, but nothing about the way any of it is covered is altogether explicit. The Church of Euthanasia set out to cause disruption and undermine the status quo, and they clearly succeeded in doing so. No One Left to Offend tells their story, and lets the audience interpret it as they see fit.

The movie doesn’t wrap up neatly; it would be a disservice to its complicated subject matter if it did. It doesn’t tell the audience how to think or what to feel about its subjects or the activities they engaged in. It’s not defined by a simple narrative about good versus evil. Some of the film is very entertaining. Some of it’s very troubling.

Among the few who’ve seen it, it’s sparked some very meaningful conversations. Some people are unwaveringly compelled by it. Of course he’s biased, but a cinephile friend of mine who’s into oddball documentaries tells me it’s one of his favorites. I have no illusions about it being a mainstream hit or ending up on Disney+, but curious people are out there, and so are people who like to be intellectually challenged and treated like adults who are capable of interpretation. Many people like to explore the outer reaches of the macabre, the comedic, the tragic, the historical, and the just plain weird in the context of the safe environment that a movie can provide.

So, why am I using my film as a case study? Let’s get into what happened with my attempts to actually get this film, which has been sitting on the shelf, finished for quite some time, released to an audience.

A Baffling Attempt at a Festival Run

The first festival I submitted to was Sundance. When informed outsiders submit to Sundance, they fully understand that they’re taking a complete shot in the dark. It’s perhaps the most competitive film festival in the world. Many of the films that are programmed there (for those not in the know, “programmed” means selected for screening in the context of film festivals) are decided upon outside of the open submission process and there are serious questions about how much nepotism plays a role in these well known, competitive festivals. Rumors abound that Sundance, along with other festivals, simply couldn’t possibly be watching all the submissions they receive in full.

In short, you don’t drop down the 50 to 120 dollars (depending on the submission category and the deadline you’re meeting) to submit to Sundance thinking that you’re going to see any return on that investment, even if your film is very good. You do it as a gamble, because there’s a miniscule, outside chance that this contribution to the most prestigious film festival in the United States might open some very real doors for you, or even put you on the proverbial “golden elevator,” allowing you to connect with serious distribution channels and people who can help you move forward on your next project. It’s an unlikely, but theoretically possible path into the small club of filmmakers who are able to consistently earn a reliable paycheck from the work they do - a potential means of pulling yourself somewhere closer to the middle of the long tail depicted at the beginning of this piece - instead of scraping by madly as a starving artist (or simply being independently wealthy).

So when, during Sundance’s deliberations in 2022, I was contacted by one of their longtime programmers - I’ll use a pseudonym and call him “Tim” because I’m not interested in directing any of the wanton ire of the internet against him - I was duly surprised. I checked to make sure the email was coming from a real Sundance.org email address. I looked Tim up to verify that he was, in fact, a programmer at Sundance. Everything checked out. He had been there for almost twenty years and his position was clearly one that involved a great deal of influence in Sundance programming decisions.

The official rationale for contacting me was to ask whether or not my film ought to be considered for Sundance’s Indie Episodic program. I had submitted it as a feature documentary. At the time, the film was cut into two parts (I’ve made a few small modifications since then and now it’s cut into three) but it was clear that Tim was seriously considering programming this film, thinking that perhaps it would be a better fit for the Episodic program than for the Feature Documentary program.

The vast majority of film festivals have a policy of providing no feedback whatsoever to films that aren’t selected, and you simply don’t get emails from these people if you’re not in the running.

Over the course of our exchange, I was told that I have “a keen awareness of matching [my] storytelling style with the story itself,” that the film was, “a fascinating story that [I] have certainly done justice to,” and that the Sundance team would, “of course consider it as a feature film that could also work for episodic.” Tim’s last words to me were, “And more importantly, just thanks for making it-- it’s such a wild ride and I hope a bigger audience is going to be able to experience it in the way that I did.”

I bided my time, and waited to see whether Sundance would decide to play the film. Ultimately, I ended up receiving the standard rejection notice on the notification date.

Now there’s nothing extremely out of the ordinary about this. There are always films that come close to being included in festivals that don’t make the cut. Many great movies are rejected from some of the most prestigious film festivals in the world every year. Only so many slots are available, and programmers unavoidably have to make difficult decisions about what to include and what to leave by the wayside.

However, over the following year, things became stranger. In addition to Sundance, I submitted the film to 30 other festivals, most of which were, of course, far less competitive and prestigious than Sundance.

Hot Docs, one of the most prominent documentary festivals in the world, reached out to me to ask me whether or not I had a shorter cut of the film – the entire piece clocks in at two hours and thirty-eight minutes. Of course the film’s runtime must have played some role in its festival fate; longer films are simply more difficult to program. Despite the recent popularity of longer blockbuster films, scheduling constraints are simply a reality at festivals. Why play one longer film when you might be able to play two shorter films? I offered up an abridged cut to approximately the second half of the festivals I submitted to, along with the full cut.

Runtime concerns aside, it nonetheless seems remarkably strange to me that any film that would be praised during the deliberation process by a programmer who’s overseen the selection process for nearly 14,000 Sundance submissions would end up with a 31 to 0 festival submission to acceptance ratio. We’re talking about a guy who’s watched thousands of the best films made over the past two decades who thought there was something worth noticing in mine. It’s flattering, of course, but it didn’t get me anywhere in terms of getting the movie off the ground.

Even my local festival, The Minneapolis - Saint Paul International Film Festival, which is known for playing longer films and premiered my previous, significantly less polished film about satirical presidential candidate Vermin Supreme back in 2014, unceremoniously passed on this one. Most of No One Left to Offend takes place in Boston, but the Boston Film Festival expressed no interest whatsoever. Chris Korda, the film’s primary protagonist, experimented with his gender identity in Provincetown in the early 90s. Surely the Provincetown International Film Festival might take some interest? Standard rejection notice once again.

Stranger perhaps still was the wall of silence I received from Tim at Sundance after he had written to me about the film in such glowing terms. Emails sent in December 2022, March 2023, and April 2024 remain unanswered. Meanwhile, in November 2023, an anonymous filmmaker concerned about whether or not Sundance had even viewed his or her film did receive a response from Tim (I’ve redacted the link that demonstrates this because I don’t want any random assholes messing with Tim; he came across as a pretty good guy to me).

Of course festival programmers lead busy lives. In the age of social media, all of us are flakier than we used to be. Tim and I are not old chums. We’ve never met in person or even had a phone conversation. I’m just one of many people whose films he appreciated during one year’s Sundance selection process. Still, why would someone who considered this a contender altogether ignore my questions about festivals where the film might be a good fit, about how I might proceed with a project that had been rejected by a dozen festivals, and then by 31? Not even a, “sorry, I can’t really provide this sort of advice, but I wish you the best of luck with the film”?

There is no smoking gun in this story, but in context, it certainly opens up some important question about how festival programming decisions are being made. We’ll get to my suspicions about what happened with No One Left of Offend’s abortive festival run soon enough, but first lets take a step back in time and look at the origins of the culture that’s taken hold in the institutional film world, and in so many American institutions more broadly, in recent years.

The Origins of Institutional Identitarian Social Justice

Throughout the 2010s, I spent a lot of time in left-leaning arts and activist circles. I had been a sort of armchair socialist from a young age, but when the Occupy Wall Street movement started to take off, I actually got off of my ass and got involved, and for a while, there appeared to be a great deal of potential in what was going on. I shot and edited 17 videos over the course of seven months covering the action and encouraging people to take part in it, on a purely volunteer basis, because I had the time to do it and believed it was the right thing to do.

People from all sorts of different backgrounds came together in hopes of developing ways to challenge a system that was funneling more and more capital and power to the top while neglecting the needs of the general population. Much of this involved the usual marches, a lot of it was generally ineffective and essentially performative, and a great deal of it happened in haphazard fits and starts, but in rare instances there were actual victories. Activists put public pressure on banks and kept people from being evicted from their homes. Millions of dollars of medical and student loan debt were purchased and forgiven. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people, were able to ask fundamental, important questions about the class structure of contemporary society that had previously been relegated to the fringes.

This all appealed to me and energized me immensely. What if we could build a future in which everybody, for the most part, got a fair shake? What if we could reduce poverty and get money out of politics? What if we could restore faith in American democracy by holding politicians and CEOs accountable for their actions? What if we could add more people to the middle class, instead of watching it collapse before our eyes?

Maybe I was naive, but if nothing else this time period did lead to the Bernie Sanders candidacy, which fundamentally changed the way class structure was discussed in the American public sphere, at least for a while. My aforementioned previous feature-length documentary, Who is Vermin Supreme? An Outsider Odyssey, largely revolved around this milieu.

As a result of my involvement, though, I also witnessed the cultural shift that took place throughout the 2010s in arts and activist circles. Slowly but surely, solidaristic attempts to challenge powerful institutions on behalf of the wellbeing of the general populace were replaced by an uptight, unreasonable, censorious, and often outright abusive culture of identitarian social justice. Dogmatic and ever-shifting rules about language and behavior were developed and new taboos were imposed on those involved. Cancel campaigns ran rampant. Well-meaning people were driven out of these movements, scenes, and milieus, often enough over allegations that were invented out of whole cloth. They were deemed guilty of social crimes that hadn’t even existed mere months before they had been accused of them, tried in social media kangaroo courts, and cast out into the social wilderness. A great deal of defamation took place, and very little of it was ever prosecuted. As is always the case with cancel culture, it was the most vulnerable who were hit hardest. Some people were able to maintain their employment and fall back on old friends. Others weren’t so lucky.

You don’t need to set too many examples in order to establish new taboos. While the ostracized and character assassinated were in the minority, most everyone else involved learned to keep quiet and walk on eggshells about any subject that could potentially be construed as controversial. The window of what constituted non-controversial conversation narrowed and narrowed. Those who knew how to take advantage of the situation managed to grab power over others by leveraging their identities and manipulating new forms of rhetoric. Manipulative opportunists thrived, taking advantage of the previously prevailing ethos of multicultural good will to engage in all sorts of convoluted forms of self serving emotional blackmail.

Most of these scenes eventually simply collapsed under the weight of these dysfunctions and now no longer exist. Those who were once involved have been scattered to the winds, and many of them have a great deal more difficulty with social trust than they did before they got involved. When I say that these experiences were genuinely traumatic for a great many people, I’m not exaggerating. A lot remains unresolved.

While the sound and fury that was present in the cultural/political zeitgeist a few years ago seems to have died down, at least for now, and given way to a kind of demoralized resignation, I think the impacts of these cultural developments have been immense. In recent years, we’ve begun living under a strange, bureaucratized form of this sort of culture. The age of cancel culture and “social justice warriors” may be coming to an end, but we’ve now entered an age of institutionalized diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Some of these initiatives have already been cut in the corporate world, because elites have begun to understand that they’re an economic, and increasingly a cultural, liability, but in the world of the arts, some of which looked approximately like the corporate world did in 2021 back in the late aughts, the identitarian social justice approach shows little sign of letting up.

A great many opportunists have effectively cancelled their way to the top. No doubt most of the people working for arts nonprofits remain well meaning people, but if the dynamics of identitarian social justice that I witnessed in the context of local arts and activism scenes throughout the 2010s are any gauge of what’s happening in these more institutionalized settings, the well meaning individuals involved are undoubtedly being manipulated and pushed around in a variety of convoluted ways by a smaller cadre of people who exhibit traits of narcissism, sociopathy, and borderline personality disorder. It would seem that the inmates are running the proverbial asylum and lately much of the world of arts nonprofits has been looking like some combination of a cult and a grifting machine. I think we’ll be dealing with the fallout of this institutional capture for years to come.

What Might Have Been Deemed Objectionable About No One Left to Offend?

So, looking at No One Left to Offend again, what might be going on here? Why the baffling mixture of praise from one of the top programmers at one of the top festivals in the world combined with the complete lack of screening invitations? Why has a film that deals with so many themes of contemporary relevance - from climate change to activism, abortion, and lgbt issues - been completely left out of the official picture thus far?

Let’s start with the scandalous stuff that I don’t think held it back with the nonprofits. The Church of Euthanasia put a great deal of effort into viciously provoking and mocking conservative Christians in general, and the Catholic Church in particular, back in the 90s. This obviously won’t sit well with most conservative Christians. Marginal exceptions aside, though, Christian Conservatives are not running independent film nonprofits. I’m not going to bring this film to the board of Focus on the Family and ask them to screen it because, of course, they will find any attention paid to these people that isn’t strictly condemning them objectionable.

What about more “normal” people? Just average filmgoers? Things are less clear here. While the movie is mostly filled with entertaining mischief and madcap antics, it does have something of an intellectual bent. It’s not a summer blockbuster and it’s not simply a fun, escapist film. It’s been described as “risky” and “difficult.”

Its protagonist also eventually has some pretty deranged things to say about the 9/11 attacks. This of course will feel disturbing and alienating to many audience members. I know it does to me. But I doubt that many people involved with independent film nonprofits are too concerned about this. After all, the sacredness assigned to the 9/11 attacks is a fundamentally conservative phenomenon, and even in right-leaning circles, the ethos of “never forget” is not nearly so powerful as it was even a decade ago.

In 2001, Chris Korda posted information on The Church of Euthanasia website about a suicide method, which was ultimately used by a woman in Missouri in 2003. Personally I think this was a stupid, reckless, condemnable thing to do, but the film does not impose this view on the viewer. I made a point to have the film reviewed by The Samaritans to ensure that I was handling the content responsibly, and I don’t think it’s possible for anyone with a conscience to leave the film with an uncomplicated view of its flawed protagonist.

True crime documentaries have been popular for years now. Unabomber: In His Own Words, available on Netflix, extensively covers Ted Kaczynski from his point of view (as an aside, some members of The Church of Euthanasia ran a “Unabomber for President” campaign in 96’, but that story never made it into the film). Audiences spent over a billion hours watching a Netflix series about Jeffrey Dahmer. It’s clear that all films do not have to be about individuals who consistently exhibit unimpeachable ethical behavior.

So what might programmers existing within a milieu defined by identitarian social justice ideology find objectionable about this film? After all, the film’s protagonists were (at least ostensibly) fighting for environmental sustainability and abortion rights. Why would the notoriously liberal world of film festivals have a problem with a film like this one?

Well, for one thing, the film’s protagonist is a problematic (and arguably narcissistic) crossdresser. Chris Korda considers himself transgender. He’s been very public about his gender identity since the early 90s, but in the film, he also questions the logic of medical transition. Why spend a lot of money and go through painful medical procedures to leave one constricting gendered identity box only to be assigned a new, and possibly equally constricting gender role, he asks? I think this is a reasonable question, but at a time when social justice liberals hold the defense of medical transition as sacred, can questions like these be publicly asked, even by transgender people themselves?

In an odd twist, the film also features animator Nina Paley, who appeared on The Jerry Springer Show with The Church of Euthanasia in 1997. In 2017, while No One Left to Offend was in production, Nina was very publicly denounced as a TERF, a “trans exclusionary radical feminist.” She was thrown under the bus and treated as a sort of scapegoat for wrong-think after sharing content that criticized developments in popular transgender ideology and discourse, starting with this New York Times article. She previously had connections with film festivals; one of her short films even screened at Sundance in 2003. She had screenings cancelled. She lost a lot of friends. She’s still dealing with the fallout of all of this today, and has even dealt with economic censorship: in early 2023, a small indiegogo campaign she ran was cancelled and refunded without any explanation from the company.

So far as I can tell, Nina is neither “trans exclusionary” nor a “radical feminist” in the first place. She’s a remarkably intelligent, amicable, thoughtful woman. These days she does a regular podcast discussing gender issues with a transwoman. But she spoke about trans issue in “the wrong” way (and continues to do so), and for years, online zealots did everything they could to whip up the sorts of fervors that would socially and professionally crush anyone associated with left-of-center politics who didn’t get in line with their program around these issues.

So Chris Korda could easily be construed as “not the representation that trans people need right now” because he’s a flawed, complicated character - either an antihero or an antivillain, depending on your interpretation - and of course this documentary also features a cancelled persona non grata from the film world, Nina Paley.

It’s important to remember that it took a while for cancel culture to really hit film festivals. Nina Paley aside, I’m unaware of any major cancel debacles pertaining to film exhibition that took place before Meg Smaker’s Jihad Rehab in 2022. Jihad Rehab (now retitled The UnRedacted) was roundly denounced as a racist, Islamophobic film by people who had never seen it. After some expensive legal rigamarole, it was able to make its premiere at Sundance, but mob pressure lead to most of Smaker’s other festival screenings being pulled, a prestigious award she was set to receive being rescinded, most of her crew asking for their names to be removed from the film’s credits, and, as is often the case for victims of ostracization, organized harassment, and mass social shaming, Smaker herself experiencing a great deal of depression and some suicidal ideation.

Some discussion of woke culture narrowing the horizons of what could be played at festivals took place in the aftermath, but it seemingly made no difference. The damage was done, and now it’s looking like film festivals are simply trying to get ahead of potential cancel campaigns as a means of preemptive damage control. The scope of what can be presented to the public at festivals appears to have narrowed significantly as a result.

Smaker was able to turn things around for her film after an interview she did with Sam Harris went viral – in fact she was able to raise almost $800k for an independent screening tour and other distribution efforts.

I don’t envy what Smaker went through. I’ve known people who’ve gone through similar experiences and I’m intimately acquainted with the effects that cancel culture can have on the mental health of individuals, the social health of scenes and communities, and the economic viability of small institutions.

Still, the question has to be asked: what of those who weren’t able to find a new path after travelling through the underworld of being cancelled in a grand, vicious spectacle of social abuse and public denunciation? What about those of us who are, so far as we can tell, just being quietly sidelined and cancelled in advance as part of less convulsive, more sophisticated PR damage control efforts? How are we to respond to this particular set of circumstances? Given the opacity of these institutions, there’s generally no way to know for sure what exactly is happening with any given artist or project, but it all begins to feel a great deal like being blacklisted.

A few weeks back, I took part in a 15 minute feedback call for The McKnight Media Artists Fellowship, which I applied to back in March. I’ve been throwing my hat into that ring for years, to no avail.

This year, I decided it was time to start being a little more honest and upfront, whether it would work against me or not. A few years ago, an optional “identity” box was added to the submission form. This was around the same time that FilmNorth, the local organization that oversees selections for the fellowship, also started doing an application workshop specifically for “BIPOC” applicants. This year, that workshop was transformed into a “QTIBIPOC” panel.

Leaving aside whether or not most of the general public is even aware of the term BIPOC, and whether the term BIPOC refers specifically to black and indigenous people of color or is simply a way of referring to all people of non-European origin while giving a special shoutout to black and indigenous people at the beginning, it’s pretty clear to me that almost no one has heard of the acronym QTIBIPOC. I pay pretty close attention to these developments (generally with some combination of amusement and despair along the way), but I had to google it myself. Luckily, Greenpeace had me covered.

So I can only assume that some “queer” people complained about not being included in the BIPOC workshop, so now we have this QTIBIPOC virtual roundtable. Whether or not “queer” even means anything anymore in these contexts is a question for another day.

In any event, this year I decided I had had just about enough of how things were playing out with these institutions, and decided to criticize identitarianism in the new identity box, knowing full well that doing so would almost inevitably turn some of the judges against me.

Based on the notes that were read to me during the feedback call, it very much seems as though the statement I included in the identity box colored the responses from this year’s panel of judges. Last year, I made a point not to rock the ideological boat much, and the notes I received then were extremely milquetoast; basically just vaguely positive stuff, but nothing particularly interesting.

This year was different, though. The most egregious comment involved me being accused of “lacking self awareness” because I “misgendered” Chris Korda in my process and history statement about No One Left to Offend. Of course Chris Korda has never cared what pronouns I use to describe him - in fact when I interviewed him he implied that he preferred that only his friends refer to him as “Chrissy” - and he says himself in the film that he now more or less lives his life as a cis heterosexual male. Even though he still cross-dresses sometimes, he questions the logic of medical transition in the film, and considers his whole approach to being trans to be something that's more about gendered balance. It’s not a popular way to “be transgender” these days, but it’s nonetheless the way Korda has conceived of himself for decades.

Admittedly four new judges are chosen for The McKnight Media Artists Fellowship each year, so the comparison with last year’s notes needs to be taken with a grain of salt, but there’s something particularly irritating and disturbing about being accused of lacking self awareness by someone in a position of power, hiding behind a veil of anonymity, who clearly lacks the self awareness and humility necessary to accept that they don’t know what the hell they’re talking about.

It’s all exceedingly tiresome and the hubris of the approach is staggering. It’s clear that some of these people genuinely believe that they’re more enlightened than everyone else, that they’re a sort of chosen vanguard, but the truth of the matter is that they’re ideologically possessed and they view life through a pinhole. And at this point there’s a whole DEI industrial complex set up to support them and maintain their lack of self awareness.

The Numbers, Inasmuch as I’ve Been Able to Find Them

Meanwhile, like I said above, one only has to open ones eyes and look at the various grids and lists of faces that so many grants, labs, and fellowships release to see that straight, white men all too often go to the bottom of the pile as a matter of course at this historical juncture. So far as I’m aware, most of these institutions don’t release much demographic information about the identities of applicants, but given what we know about Sundance submissions, I think it would pretty foolish to simply assume that white men haven’t been applying to these programs in large numbers.

Before this trend really took off, I frankly didn’t know what percentage of the American population were white men. It turns out that number is about 29 percent. It’s higher if you count mixed race men and hispanic white men.

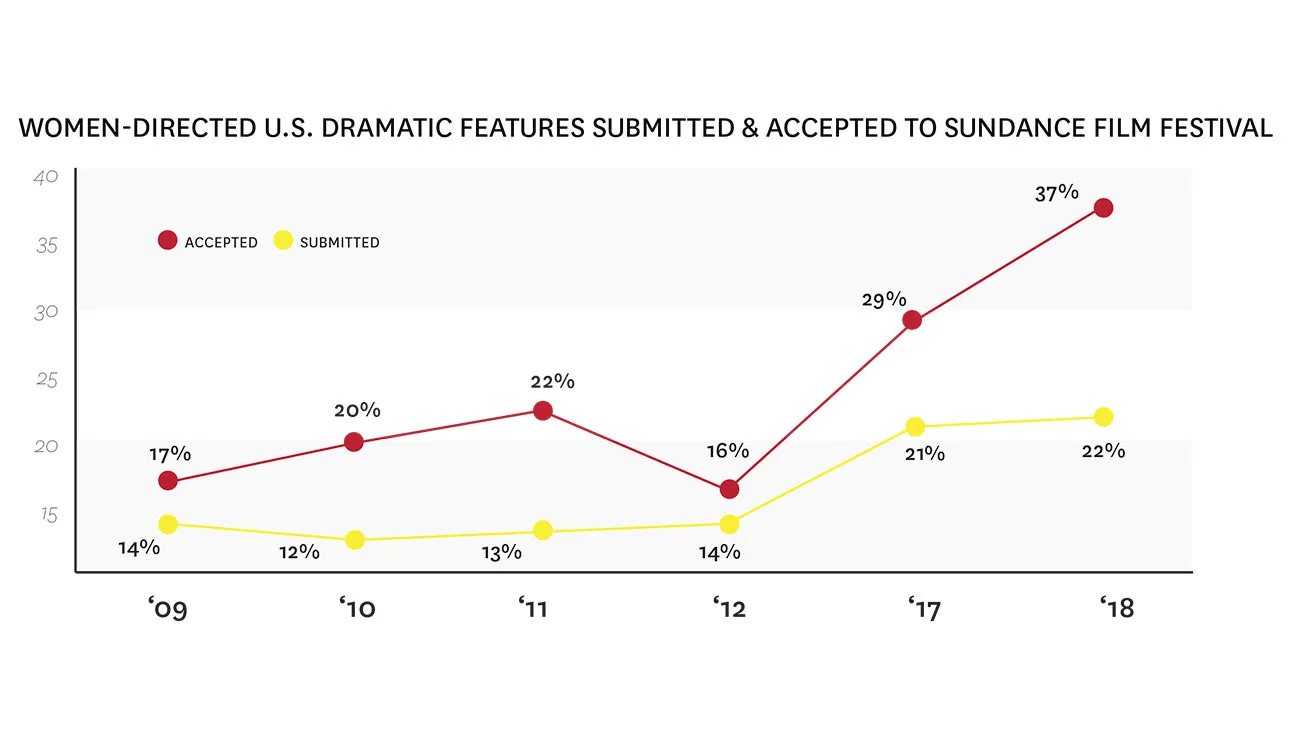

With just a little bit of digging, I discovered that Sundance has been accepting a higher percentage of US dramatic features directed by women than have been submitted by women directors since at least 2009. As of 2018, 22 percent of US dramatic feature submissions were helmed by women and 37% of US dramatic features programmed for the festival were directed by women. By 2023, women made up the majority of directors in all four of Sundance’s main competition categories. 67% of directors in the US Dramatic Competition were women, and 10 out of 11 documentary features programmed were directed or co-directed by women.

I’ve been unable to find statistics about the percentage of submitted features directed by women for years after 2018 (coincidence?), but is it sensible to assume that women are being programmed at approximately the rate at which they’re submitting these days? Given the cultural context surrounding all of this, should we simply assume that men have gotten much worse at filmmaking in recent years? Is this the identity parity that the social justice movement promised to bring us? A new protocol in which some are favored because of the boxes they check, while others are left at a significant disadvantage and edged out of the few available slots?

I did some back of the napkin math for the US directors of films featured at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival, and I’ll just say that it requires a great deal of mental gymnastics to come to the conclusions that white men were represented at parity.

Perverse Incentives

I can easily imagine DEI types insisting that No One Left to Offend “wasn’t my story to tell.” After all, I am a straight, white, male. The literary world’s “Own Voices” movement was more explicit about these matters, but there’s certainly been no shortage of people involved with the documentary world in recent years who’ve insisted that stories should be told by people who closely resemble their subjects along identitarian lines.

I don’t agree with this sort of approach. I think films should stand on their own merits - in the words of Werner Herzog, “all that matters is what ends up on the screen” - and I think there’s value in people from different backgrounds learning about one another.

But I’ve spent a great deal of time reflecting on a question: “If I had simply gotten a friend to take some pictures of me in drag, uploaded some standard social justice boilerplate about my “trans identity” to my website, come up with a feminine pseudonym, and checked the proper boxes on the festival submission forms, how might things have played out for this film?” Would it have been enough to overcome the way that someone who had been branded as a “TERF” plays a small role in the story? Would it have been enough to overcome the way that Chris Korda isn’t a simple trans underdog overcoming the standard adversity? The way that our protagonist is either a sort of antihero or antivillain, depending on how one interprets him? The way that there’s ample reason to criticize, even condemn, some of his actions and question his true motivations? The way that he discusses trans issues in a way that wouldn’t sit well with members of DEI cliques and HR departments?

What if I had simply had a trans friend pretend they directed the film? Would that have worked? I don’t like to edit my work to appeal to anyone in particular, but it wouldn’t have been too difficult to simply cut out the few, small moments in which my voice appears in the film.

What if I had pretended that my ex-girlfriend, who did a great deal to help make this film happen in the early stages, had directed this film? Would a woman director have been enough? Or I could have pretended that Lydia Eccles, who shot most of the on-the-scenes archival footage of the Church of Euthanasia back in the 90s, had directed the film.

Or what if I had played up the limited indigenous ancestry I have; after all, I am apparently 1/16th Choctaw and Cherokee. If I had simply decided to identify as a two-spirit nonbinary Choctaw/Cherokee warrior poet, would this have made me sufficiently “diverse”?

Obviously these are bizarre and absurd questions to ask, but at the same time they nonetheless appear to be reasonable and relevant questions to ask about my predicament with this film. We shouldn’t simply assume that this sort of thing hasn’t been happening for years. The incentive structure that’s been constructed as a result of these cultural shifts is a funhouse.

Discussing any of this of course remains deeply taboo in the relevant circles; the simple truth is that no substantial public discussion about these new methods of filtering who is provided with opportunity in the independent film world and who isn’t has taken place.

The Past and the Present

Like any other human endeavor, American democracy and imperial America are shot through with multilayered incongruities, contradictions, and imperfect forms of resistance against ugly structures of domination. Race is not a lens to justify sentimental stories of pure heroes of color and impure white villains or melodramatic tales of innocent victims of color and demonic white victimizers. In fact, by shattering such Manichaean (good versus evil/us versus them) views that Americans often tell about themselves, we refuse to simply flip the script and tell new lies about ourselves.

-Cornel West, Democracy Matters

Is it true that on the aggregate, white men were advantaged, in the world of film and elsewhere, for a very long time, in the United States? Undoubtedly. This country has an intensely cruel history of racism, and women were blocked from many professional opportunities for a very long time.

Does this make it right to now turn things around, “flip the script,” and discriminate against white men in the film industry while telling ourselves new lies?

Personally, I don’t think so, but so far, very little public discussion has taken place around the question. The reality of what’s happening here, the development of a new system of sexist and racist discrimination in the context of ideologically captured institutions, has been hidden behind rhetorical smokescreens for years. We need to be able to describe what’s taking place in understandable, apt terms, and institutions that are taking part in building this system need to be required to defend their program’s legitimacy. The floodgates need to be opened for a public discussion, and that’s why I’ve spent weeks writing this, and why I’m willing to risk my reputation by publishing it.

Like I said at the outset of this piece: even today, there are a great many white men at the top of the film industry hierarchy. Most directors of top Hollywood films are still men and members of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences are still predominantly men. With a little bit reading between the lines, it’s easy to see that the new program here involves solving “the problem” (too many white men in the film industry), by deliberately filtering people based on identity categories to alter the composition of those who are able to get involved in the first place. This of course creates obvious systemic barriers for younger and less established white men.

The identitarians know that they can’t remove most of the old, white men from their positions (unless they can find ways to cancel them out of the industry), so “the problem” has to be cut off at the root. Does creating a new regime of racist and sexist discrimination constitute a legitimate turn towards justice? I think it’s wrong to discriminate against people based on their race and gender. It’s clear that Martin Luther King Jr. and most civil rights luminaries agreed with me, and I suspect most contemporary Americans do as well.

Why Institutional Racist and Sexist Discrimination Are Wrong

Growing up in the 90s, I took it as a given that racist and sexist discrimination were outmoded moral evils. I simply assumed these were matters that had been settled by the general population decades before I had been born. Certainly there were some remnants of old American prejudices in segments of the population, and there still are today, but for the most part, those in favor of racist and sexist discrimination were either laughed off or censured by polite society. There’s something deeply counter-intuitive about even feeling as though I have to write this section, but it seems as though I do.

Racist and sexist discrimination arbitrarily limit and expand the opportunities available to different individuals based on factors that are beyond their control and irrelevant to whatever process they’re engaging with. In the context of cinema, these factors have nothing to do with whether or not a film tells a good story, covers new ground, or elevates the form.

Discrimination of this sort creates a playing field that isn’t level. It makes life more difficult for some and easier for others based on their (mostly) immutable characteristics and thereby decimates trust in the social contract.

For several decades, with a certain amount of affirmative action debate aside, the American consensus took this more or less for granted, and, as Coleman Hughes has repeatedly pointed out, socioeconomic class is a much better proxy for disadvantage than race is. If we want to lift up the marginalized, which I think we should, why not approach the matter through class based programs that stand a chance of actually improving the lives of large numbers of people who are living difficult lives? It seems we’ve ceased attempting to reform an economic system designed primarily to benefit the 1% that leaves far too many people struggling unnecessarily and shifted gears towards open embrace of identitarian tribalism.

Discrimination of this sort also creates new racist and sexist resentments that resemble the old ones. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the rise of identitarian social justice has coincided with a reinvigoration of old bigotries. When you tell people that their identity is the most important thing about them and that they should conceive of race and gender as eminently important, transcendent, essentialist, aspects of their being, they eventually begin to believe that these are the terms of engagement. You can tell people that they’re part of the bad and oppressive identity, and that it’s their moral duty to sit their asses down and listen and put up with whatever you want to impose upon them, but this sort of subordination can only be maintained for so long. Eventually some sort of self respect will prevail, and if that self respect emerges in the context of identitarianism, what ultimately results isn’t going to be pretty.

Right now, white nationalists, although presently very marginal, are chomping at the bit to have an identitarian movement of their own, and identitarian social justice provides ample resentment-fuel for them to work with. Some of them even explicitly want to model their future movements after the identitarian social justice movement of the 2010s. I know because I’ve read some of what they’ve written. Whether or not these more extreme reactionaries are mere paper tigers is yet to be seen - after all, they have next to no institutional power, at least outside of the way that red state governments and The Supreme Court have been gradually moving towards their positions - but I think it’s imperative that we stop stoking the frustrations that make their rhetoric compelling to people as soon as possible.

Identitarian social justice functions as a set of luxury beliefs for elite whites that allows them to assuage their guilt and signal their belonging in the upper crust, and a small number of socially climbing women, people of color, and queer people who are willing to play the proper rhetorical games and present themselves as oppressed in the expected ways have certainly been able to use it to secure educational and professional opportunities, but I know that many artists (and non-artists) that aren’t white males feel pigeonholed by this ideologically constricting state of affairs as well.

The vast majority of the population does not benefit from these policies, and that includes people of color in general; on the flipside, as Adolph Reed has repeatedly pointed out, black, hispanic, and indigenous Americans would disproportionately benefit from redistributive policies designed to uplift working Americans universally.

From a certain point of view, it’s beginning to look like devoted social justice identitarians and the old school racists and sexists are more or less on the same team. They both benefit from what’s happening here in their own ways, while the rest of us suffer for it.

The Sins of the Father

“The soul who sins shall die. The son shall not suffer for the iniquity of the father, nor the father suffer for the iniquity of the son. The righteousness of the righteous shall be upon himself, and the wickedness of the wicked shall be upon himself.”

-Ezekiel 18:19-23

I’ve never been a particularly religious person. I can remember questioning the existence of God on the school bus at the age of 6, but one thing I think Christianity got right was an insistence against intergenerational guilt.

A little while back I watched the special features on the DVD from Henri Clouzot’s classic, The Wages of Fear. At some point, apparently Clouzot drugged Brigitte Bardot for a scene in La Vérité. This is clearly wrong, and indicative of a situation in which a talented man with overly flexible scruples was able to operate with too much impunity.

I wondered to myself, am I being personally held responsible for the sins of guys like Clouzot? Or Hitchcock? For guys like Harvey Weinstein? What did I have to do with the actions of these men who abused their power, mostly long before I was born?

Is restacking the deck of domination and unfairness really the best we can do? Is this the best lesson we can take away from the ways in which power have been abused in the past? Should old systems of corruption simply be replaced with new ones?

The Importance of Cinematic Excellence and Courageous Storytelling

I’m not going to name any names, but I’ve seen some remarkably bad work receive support from nonprofits that support independent filmmaking in recent years. These awards and exhibitions were clearly not about excellent, courageous filmmaking, or socially critical work, but about people who could check the “right” boxes while conveying the “right” cultural messages.

I’m also aware of a recent competently made but remarkably mediocre short film that’s just perfect for well-to-do liberals to watch and pat themselves on the back about appreciating. The film was submitted to 40 festivals and accepted at 30. It played at Sundance. When I compare this with No One Left to Offend’s 31/0 track record, the premium that’s been placed on conforming to popular social justice narratives becomes pretty obvious to me.

These sorts of narratives pass themselves off as socially and politically critical. But are narratives that primarily function to make the professional managerial class feel good about themselves, while benefiting a small number of women and people of color who are willing to play a particular rhetorical game really critical in any way? If it all just results in siloed liberal elites being satisfied with their righteousness while most of the broader population becomes increasingly divided and downtrodden, what’s actually being accomplished here? The whole arrangement seems to function very effectively as a kind of divide-and-conquer strategy.

And what of cinematic excellence? What of film festivals being a place for untold, courageous, challenging stories that otherwise might languish in obscurity to have an opportunity to get in front of audiences, to find their way to distribution channels? What of the role of art in helping people think and feel in new ways? What of the role of the artist in condensing aspects of the world that are unknown or misunderstood into work that allows others to understand and experience, intellectually and emotionally, in novel ways?

The big festivals, like Sundance, will still of course have great films to choose from, no matter how they stack the deck along identitarian lines, because there are plenty of talented filmmakers who aren’t white men. But it’s clear that the social justice movement, in large part as a result of the way that it’s so ideologically constricting for artists from all backgrounds, has lead to lousy work being selected and celebrated as well.

And what about films that challenge the status quo? How many of them have been sidelined in recent years? How many of them simply aren’t being made in the first place, because those who might have made them simply have no way to secure the funding necessary for them to exist in the first place, and know that if they do make them, they will be roundly rejected by the institutions that might make it possible for these projects to find a wider audience?

How to Get More Opportunities for Everyone

Identitarian social justice effectively crushes any and all attempts to develop solidarity between people of different backgrounds whenever it achieves a critical mass in any given milieu. If I learned anything from Occupy Wall Street, it’s that when everyone’s fighting amongst themselves on behalf of their own tribal groups, people cannot work together to create better conditions for the broader community. In a society defined by intense wealth disparity, this is a severe problem. It’s a kind of prisoner’s dilemma. We would all do better as filmmakers (and citizens, and, for that matter, noncitizens) if we worked together to advocate for better working conditions and better opportunities for everyone, but as long as we’re all playing the oppression olympics and fighting over scraps, things will continue to get worse for all of us.

And things have gotten worse. You can see it in the sections of most major urban areas that are filled with homeless encampments. You can see it in the eyes of people who struggle to find gainful, dignified employment. You can see it in the general atomization and breakdown of trust that’s present in the population. When the general populace has no way to develop solidarity and fight on behalf of its own interests, the interests of the wealthy and powerful prevail.

The entire process is a recipe for disaster, and meanwhile, the rich just keep getting richer, while the horizons of possibility dwindle for the rest of us.

It’s not impossible to turn this ship around, but for things to change, it’s going to take more than one guy laying out his interpretation of what’s going on with film nonprofits in a 10,000+ word essay.

A big part of what gives identitarian social justice its power is the way that it’s ideologically convoluted and thereby immensely difficult to describe, and the way in which so many of its adherents have been using veiled threats for years to create new taboos and prevent anyone from accurately laying out precisely what it is and what it does. We’ve been hoodwinked, but eventually people adapt. Corrupt systems don’t last forever, no matter how convoluted they might be. Will we be able to deal with this one before a right wing reactionary system takes its place?

The Future of No One Left to Offend

In all likelihood, I’ll simply end up releasing No One Left to Offend entirely independently some time in the coming months. I may make the first part of the film available for free on my YouTube channel, and then place the whole picture behind a paywall for those who decide that they’re interested, maybe even here on Substack (although it’s unfortunate that apparently I can’t charge a one time fee for a single post here?). I’m no marketing genius and I’m not prepared to gamble my meager life savings on any sort of expensive campaign to get the film off the ground, so most likely it’ll just end up percolating in the underground for some time.

That said, if you happen to be reading this and you have ideas about effectively distributing this film, feel free to get hold of me.

Does what I’m talking about here resonate with your experiences? Is there something I’ve missed? I’m here to try to tell the truth about what appears to be happening. But arriving at and effectively articulating the truth, and, for that matter, changing institutions (or founding new ones), is, much like filmmaking, almost always a collaborative process.

Do you have ideas about moving past this impasse? By all means, discuss the matter in the comments here and wherever you can get away with doing so. It’s rare for genuine positive change to be achieved without dialogue.

Sure, it would seem that film nonprofits haven’t wanted much to do with me in recent times. But maybe there are others out there who understand where I’m coming from? Maybe new connections are waiting to be made. Maybe something new can be built.

Here’s to the future.

I imagine the barriers are even worse for filmmakers given the cost and enormous effort it takes to get a film made, and not many outlets aside from the gatekeepers.

In the literary world it’s not enough to belong to some minority group; you have to make that the point of your story. I wonder how much of this content shift is going on in film?

By the way, you can always set up a button to collect tips using something like PayPal or Buy me a coffee. Or if you want the paywall you could set the yearly subscription cost to the price of a ticket (unless there’s a limit to how low you can make this?)

It is surprising that Substack hasn’t set up a one time payment option. Especially since the workarounds people come up with are losing them money.

I agree with every word. there is a "silent majority" of people, men and women, who are afraid to say anything about this because they fear being public about concerns would be the end of their career, when in reality their career has already been taken from them because of what they are. A tearful, bitter irony.